My Pakistan: The Story of a Bishop

Title: MY Pakistan,The Story of a Bishop

Author: Dr Alexander John Malik

ILQA Publications: Lahore, 2018

Pages 246, ISBN: 978-969-640-130-8

Dr Alexander John Malik’s autobiography of sorts, My Pakistan: The Story of a Bishop, is a testament of his people, the Christians of Pakistan as well as a historical critique of Pakistan’s complicated relations to her minorities written in an emotionally gripping and intellectually challenging style. Reading it invokes a host of emotions intermingled with intellectual tensions as some of the most pressing issues facing them are incisively analysed. While Pakistan (the country) is a socio-political miracle of turning a minority into a majority, and a community into a nation, My Pakistan (the book) is a story of a young Pakistani, who stood first in University of Serampore, India (1967) in his subject (History of Religions), and then decided to leave his PhD studies incomplete at McGill University, Canada (1972), to return to Pakistan, against his family’s wishes, to stay ‘true to the oath of canonical obedience’. Thus, it is Dr Malik’s narrative of his struggles to stay true to his, rather two different types of, and often competing for devotion, loves: one for his religion – Christianity, and the other for his country – Pakistan. As the narrative is penned in first person, it becomes also an account of his spiritual journey which took him to many places all around the world but one that also drove him to his knees, and to his Lord.

Dr Alexander John Malik’s autobiography of sorts, My Pakistan: The Story of a Bishop, is a testament of his people, the Christians of Pakistan as well as a historical critique of Pakistan’s complicated relations to her minorities written in an emotionally gripping and intellectually challenging style. Reading it invokes a host of emotions intermingled with intellectual tensions as some of the most pressing issues facing them are incisively analysed. While Pakistan (the country) is a socio-political miracle of turning a minority into a majority, and a community into a nation, My Pakistan (the book) is a story of a young Pakistani, who stood first in University of Serampore, India (1967) in his subject (History of Religions), and then decided to leave his PhD studies incomplete at McGill University, Canada (1972), to return to Pakistan, against his family’s wishes, to stay ‘true to the oath of canonical obedience’. Thus, it is Dr Malik’s narrative of his struggles to stay true to his, rather two different types of, and often competing for devotion, loves: one for his religion – Christianity, and the other for his country – Pakistan. As the narrative is penned in first person, it becomes also an account of his spiritual journey which took him to many places all around the world but one that also drove him to his knees, and to his Lord.

My Pakistan is an intriguing mix of honest recollections, evaluations, ambitions, sacrifices, service to community (both Christians and non-Christians), hopes, and inadvertent involvements in politics, patriotism and a human attempt to make a sense of it all. It is also a chronology of some regrettable events and broken promises by the leaders of the country and author’s unwavering patriotism despite all these. This saga covers a period of over seven decades and is played out among people whose civilization goes back to antiquity.

The book is divided into four parts, but reads like a fluid, coherent narrative. In the first part, “Pakistan and its challenges”, the events of author’s life are intertwined with those taking place at the national level. This narration sets the scenes for the discussions that follow in the next three parts. It encompasses background of the situations that lead to the division of India into two separate countries. Along with this, the author painstakingly explains the nature of the state Quaid-e Azam Mohammad Ali Jinnah really wanted: secular not religious. His views here are laid out in a logical order, and presented in a very persuasive manner; of course no matter how persuasively the point is argued in favour of a secular Pakistan, the nation’s religious right is not going to change their stance easily and this is one intellectual battle that does not seem resolvable the foreseeable future.

The process of Islamization of Pakistan started soon after Quaid’s death, i.e. with the passing of the Objectives Resolution (07 March 1949). From then onwards, it has been all downhill for the minorities. Some Muslim religious/political parties, who originally opposed the very idea of Pakistan, have gradually hijacked the ideological narrative of the state until General Zia ul Haq completed the Islamization in the eighties. Zia’s Pakistan is poles apart from the one envisioned by Jinnah. This has been a raw deal for the non-Muslims i.e. as a result ‘the zakat, which is a religious fund, is reserved only for the Muslims’ and ‘Twenty extra marks are given to Hafiz-e-Quran to determine merit for professional colleges and even for selection for posts in the Central Superior Services’.(p113)

Another ongoing debate is about ‘two-nation theory’, which was a useful tool for acquiring Pakistan as a separate homeland for the minorities, of which Muslims were, then, the biggest. It is a little known fact that Christians (All India Christian Association) offered their unconditional support and cooperation to Mr. Jinnah and when the Boundary Commission was set up Christians demanded that for the purposes of boundary demarcation they (Christians) be counted as Muslims. The fact that the Christian leaders’ vote helped secure the present Punjab for Pakistan is better known but hardly ever acknowledged.

Despite all this the way Christians have been threatened, targeted, mistreated and attacked in Pakistan, especially after Zia’s Islamization ventures, have de facto rendered them as second class citizens. Some of these incidents have been categorized and chronologically catalogued (p.115 -134). In the coming years this information will surely serve as a record and reference and hopefully will guide the future policy makers into making sound policy decisions.

In Part two, appropriately entitled, “Despite fractured citizenship, minorities continue to serve Pakistan”, the author, in a balanced and communally fair approach, pays full credit to all religious minorities for serving and building Pakistan. He mentions many non-Christians who have contributed to the development of Pakistan like the Bhandaras, Cowasjees, and Bogas (Parsis), Sir Zafarulla Khan and Dr Abdus Salam (Ahmadis) and Jogender Nath Mandal and others (Hindus). He then focuses on those who have suffered the injustices of Pakistan’s social and political issues like Mashal Khan, a 24-year old student of Abdul Wali Khan University, Mardan, who was lynched by a mob of fellow students on alleged blasphemy (p133).

Dr Malik proudly states, ‘Thousands of high-ranking officers of the Armed Services of Pakistan, the Pakistan Air Force, and the Pakistan Navy have studied in Christian Schools/Colleges’(p154). He also presents an abridged listing of ‘some prominent educationists’, stating that not doing so will be ‘a great omission’. In addition to their illustrious contributions in the field of education and health Christians have contributed their services and sacrificed their lives in the defence of Pakistan. For this section the authors draws heavily on the research done by Azam Mairaj, and published under the (Urdu) title, Sabz wa sfed hilali parcham kay muhafiz wa shohda. The list of decorated Christian Army, Naval and Air Force officers is long and impressive (p 161-168). And reading about their courageous deeds and sacrifices fills one with both national, as well as communal, pride. Records are crystal clear that even in the field of defence Christians have been punching above their weight.

In part three, “Challenges to maintaining a balance between the heavenly and earthly citizenship” the author relates how the agitation of J. Salik entangled him into a situation where the government threatened him with an arrest. Salik was a popular Christian leader who demanded that Christians should be given time on the state media channels, and that no exams must be held on Sundays, this being their day of worship. Salik’s second demand was accepted, his popularity soared and he was later elected to the National Assembly.

Pakistan’s capital was moved from Karachi to the new, purpose-built city Islamabad in 1960. However, the ground breaking ceremony for her first proper church, St Thomas’s Church, did not take place until October 17, 1988. And even then, in response to the demonstrations against Salman Rushdie’s ‘blasphemous’ novel, The Satanic Verses, an attempt was made to demolish it when its walls were hardly six/seven feet high. Finally, after many twists and turns, the author had the honour of consecrating a part of the building on September 11, 1991, which now after completion is one of the most beautiful buildings in Islamabad.

Soon after 9/11, the USA President George Bush declared war against ‘every terrorist group of global reach’, and even though neither he, nor the then President of Pakistan Gen. Pervez Musharraf ‘consult(ed) the Christians of Pakistan’ in this matter, it was they (the Christians of Pakistan) who were punished for the events that followed. When Pakistan’s sacrifices are banded about in the war against terrorism, it must be remembered that the Christians of Pakistan have paid more than their fair share in the bargain, and have had to endure the misconceptions that they somehow represent or belong to the American side just for being Christians.

The last part, part four, entitled “The way forward” is a short conclusion, almost like a benediction, and is a resounding affirmation that Pakistan is a great country and its citizens make it a great nation. The author concludes his discourse stating, ‘I especially wish to address my co-religionists to reiterate once again: the essence of My Pakistan is that Pakistan is our country. We are the sons and daughters of Pakistan.’ This is what makes it more of a Testament of a people rather than just a biography of a priest. The book ends with the prayer of St Francis of Assisi, the most fitting way for a bishop to end any meaningful endeavour, including the writing of a book.

The task of covering over seven decades of a nation’s history, in a single volume is daunting by any standard; hence there must necessarily be omissions. As a reviewer, I have noted this to be the case in certain topics discussed. These ‘omissions’, however, do not dampen the flow of the narrative, nor the prolificity with which the matter covered is expounded. Dr Malik, has carefully chosen his tools and his materials to work with and with them has masterfully produced a coherent, concise, and yet a complete narrative. My opinions, not withstanding, in the end it is his book, and I am just a reviewer. The topics covered fit well to carry his memories and to convey his message.

My Pakistan is not the type of book to be read and shelved; it is the type to be read and to be discussed and to be contemplated upon. The author delves into issues that are of crucial importance to the Christian community, i.e. misuse of the Blasphemy Laws, kidnappings of the non-Muslim women, sale and land-grab issues of the church properties and forced conversions into Islam, the Church’s mandate to evangelise and minister and others. To this end I believe, My Pakistan: The Story of a Bishop is a valuable addition to the growing corpus of literature by the Christians of Pakistan about the Christians of Pakistan, and would highly recommend it to all those who want to understand the private pains, political aspirations and above all an unwavering patriotism of the Pakistani Christians. My Pakistan is not an assertion of owning Pakistan, but a proclamation of belonging to it in every conceivable way.

© Akhtar Injeeli 05/03/2019

Azam Mairaj’s latest book, Neglected Christian Children of Indus is, on the one hand, an album of word-portraits and an archive of losses and pains, but on the other, it is also a kaleidoscope of historical injustices and socio-political analyses of a people in search for both their identity and their destiny. In this 174 page volume the author tries to unburden a soul-suffocating emotional baggage and a weight of unresolved pains. He seems to be under a huge amount of emotional pressure to cover its many aspects in a few short pages: the rightful claim of his people to their ancestral land, in which they now live a humiliating life, the diagnosis and the prognosis of their psychological ailments, (including social inertia and self-pity), and the convoluted mental states of their so called leaders, are a few but salient aspects of his work. All of Mairaj’s characters, both the protagonists and the antagonists, in Neglected Christian Children are real. However, though not a work of fiction, the sting in the plight of its characters could be neither sharper nor deeper, nor their miseries more loathsome even if the author had created them as the figments of his imagination. Here the reality is much more convoluted and cruel than fiction could ever be. The reader meets Chacha Younus and Pa’h Farman, Younas Khokar and Michael along with several others. Each character typifies some deep-seated complex and characterises Pakistan’s present day Christian community’s denial of ownership of the real issues. Each character, in turn, grows on the reader’s nerves and clings on to his conscience without ever finding an adequate resolution. The reader is gradually drawn deeper and deeper into the web spun by the storyteller. The stories continue, but the resolution is ever evasive. This strange experience carries on even when Mairaj shifts his focus from the common characters to the special ones like J. Salik (The Sick Saviour) and Kamran Dost (Magistrate cum sweeper) and a Station Master. The problems of his subject matter, it seems, are all pervasive and of pandemic proportions, and this reviewer feels that the author finds a cathartic release in exposing them just as they are!

Azam Mairaj’s latest book, Neglected Christian Children of Indus is, on the one hand, an album of word-portraits and an archive of losses and pains, but on the other, it is also a kaleidoscope of historical injustices and socio-political analyses of a people in search for both their identity and their destiny. In this 174 page volume the author tries to unburden a soul-suffocating emotional baggage and a weight of unresolved pains. He seems to be under a huge amount of emotional pressure to cover its many aspects in a few short pages: the rightful claim of his people to their ancestral land, in which they now live a humiliating life, the diagnosis and the prognosis of their psychological ailments, (including social inertia and self-pity), and the convoluted mental states of their so called leaders, are a few but salient aspects of his work. All of Mairaj’s characters, both the protagonists and the antagonists, in Neglected Christian Children are real. However, though not a work of fiction, the sting in the plight of its characters could be neither sharper nor deeper, nor their miseries more loathsome even if the author had created them as the figments of his imagination. Here the reality is much more convoluted and cruel than fiction could ever be. The reader meets Chacha Younus and Pa’h Farman, Younas Khokar and Michael along with several others. Each character typifies some deep-seated complex and characterises Pakistan’s present day Christian community’s denial of ownership of the real issues. Each character, in turn, grows on the reader’s nerves and clings on to his conscience without ever finding an adequate resolution. The reader is gradually drawn deeper and deeper into the web spun by the storyteller. The stories continue, but the resolution is ever evasive. This strange experience carries on even when Mairaj shifts his focus from the common characters to the special ones like J. Salik (The Sick Saviour) and Kamran Dost (Magistrate cum sweeper) and a Station Master. The problems of his subject matter, it seems, are all pervasive and of pandemic proportions, and this reviewer feels that the author finds a cathartic release in exposing them just as they are! Henri J

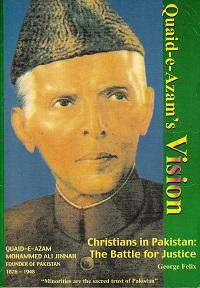

Henri J  Quaid-e-Azam’s Vision by Mr. George Felix is one of the rare works on the issue of the persecuted church in Pakistan. Mr. Felix takes pains to chronologically state the events in order to present his case for the minorities in Pakistan.

Quaid-e-Azam’s Vision by Mr. George Felix is one of the rare works on the issue of the persecuted church in Pakistan. Mr. Felix takes pains to chronologically state the events in order to present his case for the minorities in Pakistan.