Nasir Saeed

Southall: CLASS-UK, 2002

PP 54

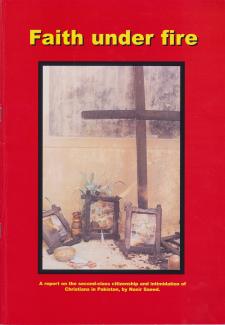

Faith under Fire is a fifty-four page report presented as a desperate attempt to draw the world’s attention to the plight of Pakistani Christians. It consists of a short Glossary, a Forward, five chapters and three Appendices.

Faith under Fire is a fifty-four page report presented as a desperate attempt to draw the world’s attention to the plight of Pakistani Christians. It consists of a short Glossary, a Forward, five chapters and three Appendices.

Having read and reflected on the report many times over, I felt compelled to share my critique and appreciation of this worthy service rendered to a hard-pressed people. These are the people Nasir Saeed belongs to and these are the people I belong to: the Christians of Pakistan.

The section entitled Glossary is a list of abbreviations and various other technical terms used in connection with the subject matter. It is a useful resource, as most of the abbreviations and non-English terms used in the report would be unfamiliar to his Western readers.

In the Forward John Hayward, who himself has first-hand experience of Pakistan, after commenting on the panoramic landscape of constitutional law-enforcement and socio-cultural issues impinging on the Christian community of Pakistan sums up his view as, ‘This is a thorough report that provides a good basis for understanding the human rights situation and attendant problems in Pakistan’.

In the Preface, the author outlines two reasons for Christian persecution in Pakistan. Firstly, the laws enacted following the amendments made to the Constitution of 1973 have dealt a serious blow to the minorities in Pakistan. ‘Most of these laws are based on sectarian interpretations and distinguish between Muslims and non-Muslims’. Secondly, is that of Christians in Pakistan being considered as ‘foreigners’ by the fundamentalists. This mind-set leads to retaliatory persecution of the Pakistani Christians if/when any Western country takes a strong action against any Muslim country or individual. Saeed decries such ‘revenge’ for presumed responsibility based on mere commonality of religion, ‘It seems that people and governments in the West do not know the price Pakistani Christians are paying for Western policies’. (emphasis supplied).

Chapter 1, entitled ‘Introduction’, comprises only of three short paragraphs commenting on one of the most quoted passages of a speech by Mohammad Ali Jinnah, the founding father of Pakistan. On 11th August 1947, just three days before Pakistan officially appeared on the world-map, the Quid-e-Azam (the Great Leader) stated:

You are free to go to your temples, you are free to go to your mosques or to any other places of worship in this state of Pakistan; you may belong to any religion or cast or creed. That has nothing to do with the business of the state.

The positioning of chapter 2, Recommendations, is anomalous in my view. It would have been better placed at the end of the discussion just before the appendices. I will postpone my comments on its contents till that point in this review. Having noted, right at the beginning, the assurance and guarantees of religious freedom for all citizens of Pakistan articulated by Mohammad Ali Jinnah, Chapter 3: Legal Context, logically follows discussing the issues of constitution, legal systems, and penal codes based on the fair and far-sighted vision of the founding father.

Chapter 4: Findings/Issues, is the main body of Saeed’s work. In here the author exposes the true nature of the Blasphemy law which is part of the Pakistan Penal Code. It includes a brief chronology of Blasphemy Laws:

1860 –The original law (Section 295) was introduced by the British Government and was aimed at providing protection to places of worship of all classes of religions living in the subcontinent. It did not contain any discriminatory clause against followers of any religion or of none.

1927 – The Section 295 was amended to include 295-A, which extended the law to include deliberate and malicious acts intended to outrage religious feelings of any class by insulting its religion or religious beliefs. These acts included malice expressed by word, either spoken or written or by visible representations insulting or attempting to insult the religion or the religious beliefs of any class. The law also stipulated punishment with imprisonment of either description for a term which may extend to ten years or with fine or with both.

1982 – A further amendment to the law (Section 295-B) was enacted under the Presidential Ordinance 1. It read: defiling the copy of Holy Qur’an. Whoever willfully defiles, damages or desecrates a copy of the Holy Qur’an or of an extract therefrom or uses it in any derogatory manner for any unlawful purpose shall be punishable with imprisonment for life. (Unlike the laws of 1860, and 1927 which were inclusive of all religions this amendment related to the holy book of only one religion, that of Muslim – reviewers note).

1986 –A further amendment was made to this law by the judgment of the Federal Shariat Court, through Criminal Law (amended) Act III, making the death penalty mandatory on conviction for the offence for desecrating the name of the Prophet Mohammad (PBUH). Here for the first time religious qualification was added to the Pakistan Penal Code, so that only a Muslim judge may hear the case under this section (Section 295-C).

Saeed, rightly, notes that both amendments B and C seem to protect the embodiment of faith of only one community, the one in clear majority and constituting the ruling class, in a multi-faith society. As these laws do not provide any protection to members of other religions, they are discriminatory. According to the majority sect, Sunnis, in Pakistan, in addition to Christians, Hindus, Buddhists and Sikhs, Ahmedis, Shias, Bahais, Zakirs, Ismailies etc. are also non-Muslims.

Included in this chapter are short discussions on other discriminatory laws like the Hadood Ordinance: Rape and Adultery, Qanoon-e-shahadat: Laws of witness and Qasis-o-diyat: blood money. The Section on Abuses against Minorities highlights the dire situation regarding issues of religious freedom, proselytization and forcible conversions. Any interfaith marriage is also a weighted issue, as from a Muslim perspective a Muslim man may marry a Christian woman but not vice-a versa. This is an area ripe for all sorts of social and legal problems.

Chapter 5 Responses to Human Rights Abuses, is a discussion of ‘responses’ by the Government of Pakistan, by fundamentalist groups, Pakistan’s Human Rights NGOs and International Agencies and Governments. In short: the Government of Pakistan has failed to react effectively to the issues, the fundamentalist groups like Jamat-e-Islami, Sipah-e-Sihaba, Lashkar-e Taiba etc., have provided confused responses stating on the one hand that Islam provides full and equal rights to the followers of other religions and simultaneously on the other clamouring for total Islamization of the country in which only Islam should survive as the sole religion. The local churches and church organizations have put up a brave front of resistance both at grass roots level as well as national and international level.

In the chapter entitled Recommendations (placed as chapter no. 2) Saeed divides his recommendations into three categories, namely: those pertaining to Legal Issues, those pertaining to Capacity building / Institutional Strengthening, and the need for Further Research.

Regarding Legal issues, the recommendations include at the very least an appropriate definition of blasphemy and a proper procedural guideline for registration (of any cases) under this law. Laws like Hadood Ordinance against women, and death sentence against children should be abolished.

The following, I feel is one of the golden nuggets Saeed has put his finger upon: adequate training is needed for the organizations trying to better the lot of the Christians; priests need to be given awareness on such laws, incidents and situations and support for work to be able to protect their communities from abuses.

Appendix 1: Sources of information & Bibliography is self-explanatory.

Appendix 2: Case Examples, is a listing of actual, name-by-name, cases of people (who have either suffered greatly or died as a result of misapplication of the laws under discussion) divided into thirteen different categories. This tragic list includes the following cases: police torture, cases desecration of churches, false accusations, land disputes, forced labour, violence against domestic servants, blasphemy, Hadood, religious freedom, proselytization, abduction and forced conversions, abuses against women and children and those relating to inter-faith marriages.

The author presents each case providing basic, essential information and reading each case has caused me to stop many times and think of our/my unfortunate brothers and sisters who have been targeted because of their faith and their low socio-economic status.

Appendix 3 is a compilation of reactions to the protest suicide of Dr John Joseph, the Catholic Bishop of Faisalabad, on 5th May 1998. On this day the Bishop took his own life using a revolver. Even though, through this act, he succeeded in drawing the world’s attention to the ever deteriorating plight of Pakistani Christians, the Pakistan authorities and some of her so-called intellectual elite refused to acknowledge the fact let alone try to understand his frustration or offer a sympathetic ear to his mourners. Some, like Mr Kunwar Intizar Muhammad Khan, a senior lawyer, shamelessly went on to claim that Dr Joseph had been assassinated by the Christians to intensify their old driver (sic) against the blasphemy laws. Reading through these absolutely ludicrous reactions left me in a strange position where one has neither the strength to cry nor the will to laugh.

Regrettably, the report is not totally free of typographical errors and one case; 2.11.10 (p 48) Robina James, has been mistakenly duplicated as 2.11.11 (p 49). I sincerely hope that these minor details will be appropriately attended to in subsequent editions.

Nasir Saeed, a freelance journalist, a passionate human rights lobbyist, an ethnic Pakistani and a Christian by religion, is fully qualified to write the above reviewed report. To add authenticity and ensure the accurate portrayal of ground realities the author in keeping with the true journalistic traditions, made a special trip to Pakistan to double check and verify his facts and figures before committing them to the public domain. I, as a member of the same community, deem it a privilege to offer a critique of the work for my readers. I further hope that it will be read by many more and sincerely hope that those in echelons of power and domains of influence will take some notice of the facts presented in it.

Addendum

It is worth noting that in Pakistan prior to 1986 only 14 cases pertaining to blasphemy were reported; however between 1986 and 2010 an estimated number of 1, 274 people have been charged under these laws. (Source Dawn.com).

(URL: http://dawn.com/news/750512/timeline-accused-under-the-blasphemy-law)

© Akhtar Injeeli 31/10/2014