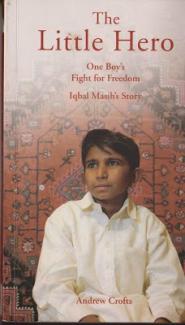

Iqbal Masih's Story (1983 - 1995)

Andrew Crofts

Vision Paperbacks, London, 2006

ISBN: 13:978-1-904132-84-4

ISBN: 10:904132-84-7

PP 246

The following review, by Akhtar Injeeli, has also appeared in The Saawan International magazine

(Sept. 2014 Vol. 26, No. 09, published from Lahore, Pakistan)

Few children in the world have affected their nation’s conscience in the way Iqbal Masih, a little Christian boy of Muridke ( a village near Gujranwala, the Punjab) was able to do for Pakistan. His humble beginnings, undaunting courage and his extra-ordinary oratorical skills provided him the opportunity to represent millions of Pakistani Children in Europe and America. These very qualities also made him a marked boy. To Europe and America he became a symbol of Pakistan’s poor children who never have, let alone enjoy, their childhood. His steep rise from abject poverty to the spotlight of western media and the centre stage of human rights organizations made many highly successful ‘business men’ very nervous. The question was not if, but when would these slave traders, money changers and thugs, masquerading as business elite of Pakistan, get him. When they finally did, he was only twelve years old. The deafening bang of assassin’s shot-gun that ended our little hero’s life on April 16 1995 in the open fields of the Punjab has not been able to end the mission for which he paid with his blood.

Few children in the world have affected their nation’s conscience in the way Iqbal Masih, a little Christian boy of Muridke ( a village near Gujranwala, the Punjab) was able to do for Pakistan. His humble beginnings, undaunting courage and his extra-ordinary oratorical skills provided him the opportunity to represent millions of Pakistani Children in Europe and America. These very qualities also made him a marked boy. To Europe and America he became a symbol of Pakistan’s poor children who never have, let alone enjoy, their childhood. His steep rise from abject poverty to the spotlight of western media and the centre stage of human rights organizations made many highly successful ‘business men’ very nervous. The question was not if, but when would these slave traders, money changers and thugs, masquerading as business elite of Pakistan, get him. When they finally did, he was only twelve years old. The deafening bang of assassin’s shot-gun that ended our little hero’s life on April 16 1995 in the open fields of the Punjab has not been able to end the mission for which he paid with his blood.

Iqbal Masih, like hundreds of thousands of other poor Pakistani Children started his working life, as a slave (though no one in his community or country uses this term in such contexts), at the tender age of four, weaving carpets which kept families like his at bare survival level while making the likes of his masters richer with each successful sale of craftsmanship highly sought after in the effluent western countries.

Through the story of Iqbal Masih the world learned how costly in reality these cheap Pakistani (often sold in the west as Iranian) carpets were. Unfortunately his legacy seems to be fading away fast in the glitter and glamour of headline grabbing, politically expedient, fast moving media events. The vacuum created by the role-model image of innocence and courage will undoubtedly be filled by others. His own people have neither had the courage, nor the conviction, to give this modern day David the due which he rightfully deserves for challenging the Goliaths of this age. And I, being one of his own people feel that pain, and shame for the lack of decency exhibited by our leaders and intellectual elite to secure a rightful place for this fallen hero in the pages of history. The author of his story, Andrew Crofts (a ghost-writer), has thus rendered an invaluable service to Pakistan, as a whole, in general and to the Pakistan’s children, in particular by piecing together in a skilful narrative the story of Iqbal Masih. His labour of love, I hope, will help the readers’ focus their attention on the value of each of the millions of children employed in the carpet making industry in countries like Pakistan. He has also preserved for future generations a story which should not be forgotten, but instead should be narrated over and over again to instil pride and courage in a people who have a habit of forgetting their past giants in short-sighted attempts of chasing the looming shadows of their present dwarfs; often claiming to be their leaders.

Iqbal came from a typical village family, son of illiterate parents, Inayat Bibi and Saif Masih, a manual farm-hand who, due to lack of livelihood, had started using drugs. Iqbal’s little sister, Sobya, appears several times in the narrative and adds a dimension to his caring nature. Whenever, Iqbal saw younger girls being mistreated he always thought of Sobya. There are thousands of such Iqbals, with thousands of Sobya’s in Pakistan working in unspeakable situations.

Iqbal, on his second attempt, successfully escaped from the clutches of his masters and wanted to do something for the children in similar circumstances around Pakistan. Someone in Lahore had been thinking on similar lines but in a much more organized and pragmatic manner. Ehsan Khan, had during his studies at a local university envisioned an organization for this purpose and had founded Bonded Labour Liberation Federation (BLLF) in Lahore. It had its office and a Freedom campus where children were kept safe, looked after and educated. While on the streets and scrounging for food Iqbal had serendipitously encountered Ehsan Khan, who was addressing a rally promoting freedom from bonded labour based on a bill the government had recently passed; this meeting was to change the destinies of both. Iqbal found shelter under the mentorship of Ehsan Khan and went to live, be educated by, and work for BLLF in Lahore.

During his stay in Lahore Iqbal learned to read and write, and to speak to people with radiance and confidence that marked him out for greater things in the future. He also picked up courage to articulate his convictions and participate in raids on several illegal factories, carpet houses and brick kilns. He became instrumental in encouraging hundreds of children to break free from the life of bonded labour. It was little surprise then that his mentor Ehsan Khan took him to Stockholm, Sweden, to represent and speak for these slaves.

The invitation to represent BLLF at the Stockholm meeting had its roots in an earlier event which Ehsan Khan had attended in Vienna. It was here that while promoting the work of BLLF, he had caught the eye of Doug Cahn form the Reebok Human Rights Foundation based in America. This short encounter, followed by a along-drawn correspondence between the two men eventuated in Iqbal Masih not only attending, but also addressing the conference in Stockholm. This conference was organized by various interested parties to raise awareness in Europe that slavery still exists. Our Iqbal addressed the audience of several thousands holding up the beating comb and the pen. He eloquently and persuasively impressed the audience about where he believed the future of his nation’s children lay. He thus did not only win the Reebok Human Rights Award, which is awarded to young people who have made substantial contributions to human rights in non-violent ways, but also a scholarship to study at the Boston University. But above and beyond all this he won the hearts of many who would always admire and love him. These well-wishers arranged for him to visit America and address several school assemblies to raise awareness of slavery which still exits in many parts of the world under various guises and pseudonyms. He had also been promised in form of a scholarship a future to help change all that.

That was the bright future for which Iqbal now lived, a future which he did not live to experience. While in Sweden he was examined by the doctors who, judging from his x-rays, concluded that he was only eleven or twelve years old. This fact became a crucial matter, when after his tragic assassination; the carpet mafia claimed baselessly that he was a midget of nearly twenty years, whom Ehsan Khan had cleverly used to his own ends.

Our little hero, Iqbal Masih, was sent back-breaking labour in exchange for the money his half-brother needed to get married. Unfortunately, loans acquired through such arrangements and intended to be paid off by children’s labour, can never really be paid off. Poverty, illiteracy, incompetency of law enforcing agencies i.e. the local police, and fear of hired thugs to settle scores on every conceivable physical level, create a socio-economic environment in which the carpet mafia and the brick-kiln owners thrive by intimidation and use of brute force, denying even the most basic of human rights to their workers, thus systematically robbing children of their childhood, women of their honour, men of their dignity and successive generations of their chances of ever breaking free from the shekels of slavery. Like the bricks they make, these slaves are treated as nothing more than lumps of clay to be baked and used to pave the roads and be trodden upon like the foot paths they make or like the carpets they weave. Their skill and craftsmanship definitely brings wealth to their masters and grace and comfort to the homes where their handicrafts finally end, but nothing but misery, heartache, and even sudden death to them, the craftsmen; such are the ground realities. Reading The Little Hero makes these ground realities come to life and administer a ‘reality slap’ to the reader. A reality slap that I hope will bring Iqbal Masih’s message to thousands more through this masterly narrated saga of an extra-ordinary, not-to-be-forgotten boy.

I am aware of the baseless arguments and unsubstantiated claims that have been put forward to discredit Iqbal Masih for his astounding accomplishments. Of course, the carpet industry, the brick kilns owners and the manufacturers of cheaply produced high quality sporting goods have had their businesses effected. These groups, with vested interests have proved historically not only to be bad masters, but also bad looser. Instead of licking their wounds and reflecting upon and being ashamed of their antics, after his tragic death they have taken to every means at their disposal to rob him of his legacy.

For me as a Pakistani, I would always remember of two Iqbals in connection with Pakistan:

Firstly Dr Mohammad Iqbal, the revolutionary poet-philosopher, who dreamed of a free homeland but did not live to breath in its freedom, and secondly Iqbal Masih who dreamed of a brighter and fairer Pakistan with equal opportunities to all its citizens, who unfortunately also like his name-sake did not live to see the day.

© Akhtar Injeeli 01/11/2014