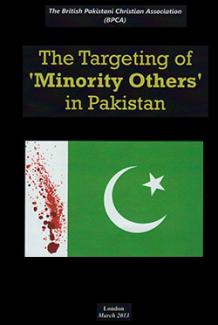

The Targeting of 'Minority Others' in Pakistan

The Christian Minority in Pakistan: Problems and Prospects

The Christian Minority in Pakistan is a concise profile, as well as a compact socio-political analysis, of the Christian Community in Pakistan. The book can be divided into three parts (my divisions):

The Christian Minority in Pakistan is a concise profile, as well as a compact socio-political analysis, of the Christian Community in Pakistan. The book can be divided into three parts (my divisions):

1. Historical context (first three chapters) 2. The problems (chapters four, five and six) 3. Prospects and proposed solutions (chapters six and seven)

Asimi starts his thesis by doubting and/or outright denying the arrival of Apostle Thomas to India within the first Christian century. According to him, the first introduction of Christianity to the sub-continent was by the Roman Catholic Fathers in the late sixteenth/early seventeenth century and did not succeed well even at this later date as, for all practical purposes, Christianity failed to take root in India.

The (more successful) reintroduction of Christianity, according to Asimi, is linked with the British Raj. In 1600 East India Company (EIC), owned by private citizens, started its operations with the sole aim of growth of trade and resolutely adopted a policy of avoiding any kind of Christian pursuit. The company’s activities gradually expanded into politico-military sphere. By 1857 it effectively controlled the political landscape of vast Indian territories. The (so called) Sepoy Mutiny of that year was the last concerted effort by the Indians to regain self-governance and is recorded by their historians as The war of Independence, albeit a failed one.

On first September 1958 India was placed under the direct rule of the British Crown and stayed so until 14th/15th August 1947, when the British left it divided into an independent India and an independent Pakistan. The political subjugation of nearly three and a half centuries by the British left a bad taste in the mouths of most Indians. Though India had enjoyed some benefits from the Raj, for the most part the natives resented it. The foreigners left behind them some permanent reminders of their domination in the form of tall-steepled churches, Christian hospitals and educational institutions, as well as a small minority of Christians who practised, mostly a western style, Christianity. Asimi notes: Most of the non-Christian population looks upon all this as an alien legacy left behind by an alien power. They were averse to this power then, and they are averse to its legacy today. (p 3). The rest of the book discusses the plight of Christians in Pakistan through this resented image.

Asimi divides the problems of the Christians in Pakistan – who according to him, make up 1.9% of the population (p 113) – into the following three broad categories. Firstly there is a serious lack of unity and cohesion in Christians. The main divide being between the Catholics and the Protestants, but then there are innumerable divisions within the Protestants, and this religious factionalism spills over into secular and national life. Secondly, there is a ‘sickening lack of effective secular leadership’ and this ‘is the greatest weakness of Christian Minority in Pakistan’ (p 116). Finally, there is a lack of integration of Christians into the socio-cultural milieu of the land, which according to the author, is the most serious part of the negative image of Christianity.

In the concluding chapters of his work, Asimi presents a set of prospects and solutions, which are a welcome addition to the debate about the plight of Christians in Pakistan, but cannot be swallowed wholesale by this reviewer.

My own studies and the evidence available to me lead me to radically different conclusions about the earliest introduction of Christianity to the Indian sub-continent as well as to the history of its Christian Church. I also do not agree to the figure of 1.9 % as being representative of Christian population in Pakistan (I believe the figure to be significantly higher), but as these two issues are not the main substance of Asimi’s thesis, I will refrain from commenting on them further.

The main point of the book is about identifying the problems of the Christians in Pakistan and offering a set of workable solutions, and it is this part that I would like to peruse here.

That ‘Christianity in Pakistan must have a Pakistani face’ is a valid and in fact a laudable suggestion and no one wants to dispute it. And I, for one, can even accept that, ‘The kind of confrontational/evangelical Christianity that was brought to the Indian-sub-continent by the West should become a thing of the past’ (p 148). However, it needs to be firmly established that Christianity predates the state of Pakistan and that its followers hold on to certain non-negotiable tenets: the irreducible minimums of the Christian faith. These cannot, and must not, be sacrificed in an attempt to produce a so called ‘Islam-Reconciled Christianity’.

For example it appears that Asimi, under the influence of modern western scholarship, is willing to reconsider the sacrificial death of Lord Jesus Christ. On p 154 he enlists three views of Jesus’s crucifiction; the Jewish view was that his close companions ‘stole his dead body, concealed it, and spread the false news that He had risen from the dead’ (emphasis is mine). The Christian faith’s declaration that he ‘rose from the grave on the third day; ascended into heaven, now sits on the right hand of God and, in the fullness of time, will come again to judge the good and the bad’ is labelled as ‘The tradition that was created and was strenuously promoted among His few diehard followers’ (emphasis is mine). What is crucial here is that Asimi after mentioning the two above versions of the crucifixion and resurrection events, states that the ‘tradition which the Muslims follow is that, Roman soldiers …mistakenly arrested a man who did, or had been made to, look like Hazarat Issa… and hung on the cross a common man in place of Hazrat Issa’. The disturbing part of this discussion, for me, is the author’s assertion of this to be ‘The very plausible tradition’ (emphasis is mine). As stated above, while there is no serious harm in claimants of Christian faith in dressing in local/traditional attire, and modifying their worship styles to adapt to more eastern traditions, we as Christians cannot compromise the most fundamental doctrinal tenets of our faith to produce an ‘Islam-Reconciled Christianity’. In fact, any form of so called ‘Christianity’ which denies the sacrificial mission of Christ is anything but Christianity. Asimi asserts ‘The Jesus of old orthodoxy is being replaced by a Jesus of history and humanity’ (p164) and echoes the statement of Anglican Bishop Spong, quoting him in his book “Christianity must change or die”(p.165). This reviewer would like to add his own sentiments here that, in an attempt to change Christianity let us not attempt to change the Christ of history and the Lord of our faith, as doing so will mean we die!(that is in every conceivable way).

For the purposes of this review, having pointed out the most important of the theological concerns, I would refrain from discussing other less weightier matters in this regard. Asimi’s theology aside, he does have some practical suggestions about the ground realities faced by Pakistani Christians. His advice, based on 2 Corinthians chapter 5 to be faithful and obedient to the government of time and to practice a ‘works orientated Christianity’ to become more relevant to the national milieu as, ‘Islam itself is a religion of works’ is worth consideration. This reviewer believes that over time the emphasis on salvation by faith alone has not been misplaced; however adding a greater emphasis to pursuing practical Christianity by committing charitable acts is a laudable goal.

Asimi while discussing the Challenges and choices facing the Christian community points out that ‘a prerequisite to any successful communal leadership is the development of clearly defined and achievable communal goals’ (This emphasis is author’s and this reviewer fully agrees). On p 127, he proposes the creation of a Christian Community Leadership Council (CCLC) ‘or something akin to it’.

He also points out that competitive leadership has proven ineffectual, and suggests that this proposed body ‘should be the sole vice o the Christian community in all secular maters. And that in his view one of the first concerns of the leadership Council should be to seek international recognition for the Christians of Pakistan as an “insufficiently protected minority” and set up a Christian Legal Defence Fund. The broad methodology of proceeding with this framework is outlined in the rest of the chapter under consideration.

This reviewer’s overall impression of the book is that it fails the litmus test for orthodox Christianity and kowtows to a theological mishmash to improve the Christians’ acceptability among the Muslims by adopting a somewhat diluted version of their faith, labelling it as ‘Islam Reconciled Christianity’. The reviewer’s view point here would be to, instead, create an agreement to disagree document, and then work with whatever can be accommodated on both sides.

Asimi, does raise some very valid points about the wordings used in Pakistan’s constitution and the way the so called blasphemy laws are effecting the lives of Pakistani Christians. His overall assessment of the quantum of the unfairness meted to his people and his socio-political insights are both incisive and deep and I feel that the intellectuals of the Christian community of Pakistan would do well to give his proposals a fair and comprehensive consideration. As clear from the above review, this reviewer has serious reservations on the author’s historicity, statistical analyses and theological interpretations but has found that his identification of the problems and proposed solutions do add significantly to the debate about the Pakistani Christians’ future.

Akhtar Injeeli

On May 6 1998, at 9:30 pm, Dr John Joseph, the Catholic Bishop of Faisalabad, Pakistan, committed suicide in front of a Court in Faisalabad that had sentenced a Pakistani Christian man (Ayub Masih) for alleged blasphemy. The Bishop's last words, just as he pulled the trigger of the gun held to his own temple, were addressed to him: "Ayub I am offering my life for you".

On May 6 1998, at 9:30 pm, Dr John Joseph, the Catholic Bishop of Faisalabad, Pakistan, committed suicide in front of a Court in Faisalabad that had sentenced a Pakistani Christian man (Ayub Masih) for alleged blasphemy. The Bishop's last words, just as he pulled the trigger of the gun held to his own temple, were addressed to him: "Ayub I am offering my life for you". The Christian Minority in Pakistan is a concise profile, as well as a compact socio-political analysis, of the Christian Community in Pakistan. The book can be divided into three parts (my divisions):

The Christian Minority in Pakistan is a concise profile, as well as a compact socio-political analysis, of the Christian Community in Pakistan. The book can be divided into three parts (my divisions):